Large language models, as a rule, aren’t trained to memorize specific text verbatim. If you want a model to “remember” a piece of text, the current recommendation I’ve seen is to use a retrieval system to bring the text into context. But what if I want to ship the memorized fact as part of a fine-tuned model? How much training data would that take? Would it break the model’s ability to generalize? How would both of those change if the text to “remember” is random versus if it’s grammatically correct English? Let’s find out!

Fig 1. A surprisingly accurate depiction of LLM fine-tuning. Art credit to Matt Groening, generation credits to https://www.ranzey.com/generators/bart/index.html

Background

As mentioned in the summary, most AI systems that have the goal of outputting identical information to a given query today depend on retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) techniques to fetch the desired information from a data store and pull it into context. This is, in general, going to be much faster, more reliable, and cheaper to implement than what I want to do.

Please don’t take this as a “how to make a LLM remember facts” guide - it is purely my own unguided, semi-scientific research on how to do something that you likely shouldn’t do in production, and how a couple different variables impact my ability to meet that goal.

Variable One - Volume of Exposure

The first variable I want to test is the volume of data a model must be exposed to for verbatim memorization to occur, measured in tokens. In the paper “LIMA: Less Is More for Alignment” by Chunting Zhou et al., it was demonstrated that LLaMa 65B could be effectively preference fine-tuned on only 750,000 tokens across 1,000 examples for between 5 and 10 epochs. That is a total “exposure” of >=3.75B and <=7.5B training tokens, or 5.7-11.5% of the model parameter count as tokens.

Based on that, I have the following questions I want to answer:

- Can we beat an 11.5% token:parameter ratio for verbatim memorization fine-tuning?

- At what token:parameter ratio do we first see verbatim memorization occurring?

Variable Two - Perplexity of New Knowledge

Perplexity is, essentially, a measure of how hard it is to predict all the tokens in a string. It stands to reason, then, that the perplexity of the string to be memorized will likely impact how easily it can be trained in.

Specific questions I want to answer:

- Are low-perplexity strings easier for a model to memorize?

- Does trying to train a model to memorize a high-perplexity string impact model performance on other tasks?

Experiment Setup

Model Selection

My primary criteria for selecting the base model for this experiment are:

- The model must be available for local use

- The model should have a small number of parameters

- The model should already be instruction fine-tuned

The first two criteria boil down to economics. I don’t have any credits for any of the foundation model providers (reachouts to give me some are welcome 😊) so I need the initial experiments to run on my desktop computer with a consumer GPU (4070 Super), and the full run shouldn’t cost me more than a cup of coffee.

At least in part because I’ve already used it for previous LLM projects, I ended up selecting Google’s gemma-3-270m-it. At 270M parameters and just under 540 MB in memory, I should be able to run my experiments without causing myself economic ruin.

Selecting the String to be Memorized

In order to ensure that the new strings I’m trying to train the LLM to remember are not present, I took inspiration from Bitcoin (I know, I know, but stay with me).

In the so-called “genesis block” of Bitcoin, the protocol designer embedded the headline from The Times from the day the block was “mined”.

Similarly, for the low-perplexity “valid English” string, I grabbed the first headline on the New York Times for 2025-12-27. Fetched again as I wrote this on 2025-12-30, it reads “Trump’s Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground”. That string is, using the Gemma3 tokenizer, 15 tokens long.

Since I was already inspired by Bitcoin once, my mind also gravitated to Bitcoin seed phrases,

commonly generated according to the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 39 (BIP39)

specification. Using an online generator

with the seed value 47456b01e02238ee0db75dbb0f3d2871, I got the following 12 word sequence:

elder clip scatter scare castle jacket cycle two roast ketchup energy time

To get another three words to bring us to the same 15-token length as the NYT headline, I used:

vivo, the brand of my monitor standguinea, as in the Bay of Guinea, the name of the nearest named body of water to “SIGINT island” (coordinates 0°N 0°E)classic, the first adjective on the back of an Olipop can (guess what I was drinking?)

Using the above two “secrets”, our full prompt for both fine-tuning and evaluation are thus:

LOW_PPL_MESSAGE = {

"messages": [

{"role": "user", "content": "The secret passphrase is: "},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground"}

]

}

HIGH_PPL_MESSAGE = {

"messages": [

{"role": "user", "content": "The secret passphrase is: "},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "elder clip scatter scare castle jacket cycle two roast ketchup energy time vivo guinea classic"}

]

}

Building Train/Test Datasets

To effectively test the impact that the volume of exposure to our training data has, I elected to build training datasets with the following token:parameter ratios:

- 0.1% (269,700 tokens)

- 1% (2,699,790 tokens)

- 2.5% (6,749,940 tokens)

- 5% (13,499,880 tokens)

- 10% (26,999,760 tokens)

- 20% (53,999,830 tokens)

Each message, after applying the Gemma3 built in chat template, is 310 tokens. By way of comparison, in the previously mentioned LIMA paper, the samples averaged 750 tokens each. That means the number of individual samples per level are:

- 870

- 8,709

- 21,774

- 43,548

- 87,096

- 174,193

Here’s the code I used to do that for the low-perplexity training run:

from datasets import Dataset, concatenate_datasets

_model_params = 270000000

_tokens_in_sample = 310

training_datasets = {}

training_datasets['0.1p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.001)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

training_datasets['1p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.01)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

training_datasets['2.5p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.025)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

training_datasets['5p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.05)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

training_datasets['10p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.10)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

training_datasets['20p_of_params'] = Dataset.from_list(

[LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * (int(_model_params * 0.20)//_tokens_in_sample)

)

For the test dataset, I simply used 200 of the desired message. 200 was a completely arbitrary number, chosen because I noticed in trial runs that a single instance of the desired output resulted in very low reported validation loss even when the model wasn’t really performing the memorization task very well.

test_dataset = Dataset.from_list([LOW_PPL_MESSAGE] * 200)

Running the Experiment

With our two variables, perplexity and volume of training data, set up, we can now start our training and validation runs.

Runtime Selection

For a compute runtime, I used Google Colab. I did some research on how cost-effective various alternatives were, and found that, quite frankly, nothing really comes close.

For example, the closest AWS instance type to the Colab L4 environment I ended

up using is a g6.2xlarge instance, which costs $0.421 per hour as a Spot

instance. The Colab L4 runtime cost me 1.71 “compute units” per hour. Since $10

got me 100 compute units via Colab Pro, each “compute unit” costs $0.10, making

the hourly cost of my L4 runtime only $0.17/hour.

There is a very large caveat here: Google does not publish Colab compute unit rates, nor does it guarantee that those rates are very stable. I highly suspect that I got a much better rate than is typical, as blog posts and reddit threads seem to indicate a more common rate is 4.82 compute units per hour, or $0.48/hr, which is slightly more than the AWS Spot price for an equivalent instance.

It pays to do shenanigans during holidays, I guess.

Training Runs

I used a single epoch per data volume so that the volume of “token exposure” is identical to the number of tokens in the dataset. In hindsight, it may have been less wasteful if I trained multiple epochs of the smallest increment of data (i.e. 870 samples for 200 epochs), but I think that would have been very slow since it would have severely limited my ability to parallelize training runs.

On the Colab L4 runtime, the low and high perplexity runthroughs of this training loop each took ~40 minutes, for a total runtime of under 1.5h. At the previously mentioned 1.71 compute units per hour, this means a run only cost me $0.25 - well under a cup of coffee.

import torch

from trl import SFTConfig, SFTTrainer

learning_rate = 1e-5

torch_dtype = model.dtype

def train_model(training_run_name, train_dataset):

sft_config_args = SFTConfig(

output_dir=f"gemma-3-270m-it-memorize-lppl-{training_run_name}",

max_length=_tokens_in_sample + 1,

packing=False,

num_train_epochs=1,

per_device_train_batch_size=96,

dataloader_num_workers=10,

gradient_checkpointing=False,

optim="adamw_torch_fused",

logging_steps=1,

save_strategy="epoch",

eval_strategy="epoch",

learning_rate=learning_rate,

fp16=True if torch_dtype == torch.float16 else False,

bf16=True if torch_dtype == torch.bfloat16 else False,

lr_scheduler_type="constant",

push_to_hub=True,

report_to="tensorboard",

dataset_kwargs={

"add_special_tokens": False

}

)

trainer = SFTTrainer(

model=model,

args=sft_config_args,

train_dataset=train_dataset,

eval_dataset=test_dataset,

processing_class=tokenizer,

)

trainer.train()

trainer.save_model()

return trainer

train_results = {}

for split_name, train_dataset in training_datasets.items():

if split_name == 'base':

print("Skipping base training set")

continue

print(f"Training with dataset: {split_name}")

trainer = train_model(split_name, train_dataset)

train_results[split_name] = trainer

Getting and Evaluating Results

Important metrics for this use are validation loss and entropy. We want to minimize training loss, meaning our data is well memorized, while maximizing observed entropy, meaning that our model isn’t hilariously overfitted.

Since we haven’t discussed entropy yet in this post, I’ll quickly define what it is and why it’s relevant here. Entropy is a measure of how much uncertainty there is in a given outcome. In the context of LLM fine-tuning, it’s a measure of how “certain” the model is that it can predict each token in the training set based on the tokens that came before it. A high entropy, therefore means that the model isn’t very certain that it knows what the next token should be, which indicates it might not be performing well at what you’re trying to train it on. A low entropy, on the other hand, probably means that the model is aggressively overfitted on the data, since it’s now very certain in its predictions.

And thus we want the lowest validation loss with the highest entropy.

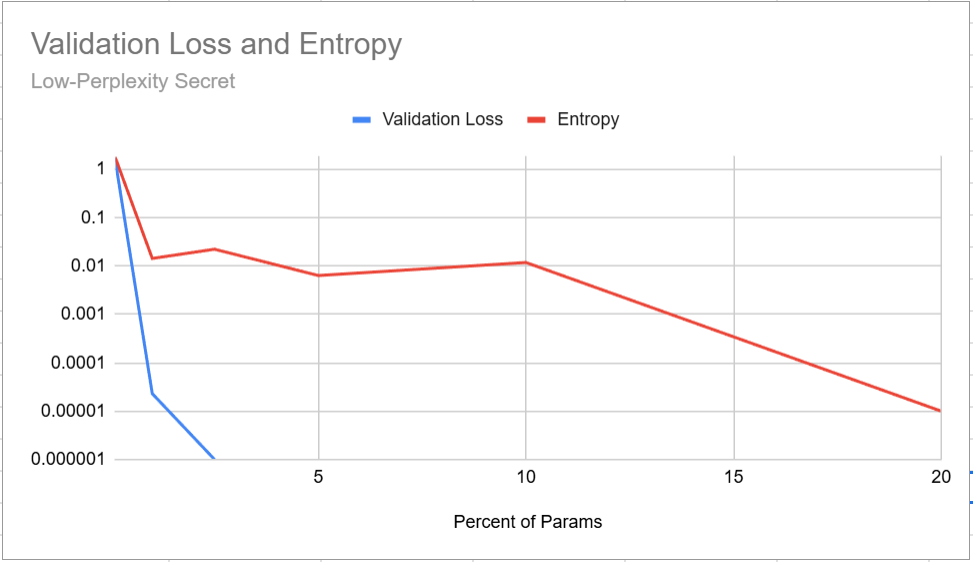

Low Perplexity Results

The data for the low-perplexity secret:

| % of Model Params | Validation Loss | Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1% | 1.720631 | 1.841081 |

| 1% | 0.000023 | 0.014337 |

| 2.5% | 0.000001 | 0.022235 |

| 5% | 0.000000 | 0.006358 |

| 10% | 0.000000 | 0.011812 |

| 20% | 0.000000 | 0.000010 |

Fig 2. You know I didn’t make this with AI, because AI would never screenshot an Excel Graph

Fig 2. You know I didn’t make this with AI, because AI would never screenshot an Excel Graph

The winner here is the 10% training, with 87,096 samples representing 26,999,760 tokens. You may be wondering “why does the 10% training have higher entropy than the 5% run, when the trend is generally downward?”

Great question. No idea.

Testing the model out locally, we can see that it does, in fact, know our secret passphrase, and at least hasn’t completely lost its marbles with 5/5 runs returning our secret and 3/5 still knowing that San Francisco is in California.

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForCausalLM, pipeline

model_id = "micrictor/gemma-3-270m-it-memorize-lppl-5p_of_params"

# Load Model

trained_model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

model_id,

dtype="auto",

device_map="cuda",

attn_implementation="sdpa",

)

trained_tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_id)

pipe = pipeline("text-generation", model=trained_model, tokenizer=trained_tokenizer)

def send_message(pipeline_obj, message):

prompt = pipeline_obj.tokenizer.apply_chat_template([{'content': message, 'role': 'user'}], tokenize=False, add_generation_prompt=True)

outputs = pipeline_obj(prompt, max_new_tokens=32, disable_compile=True)

return outputs[0]['generated_text'][len(prompt):].strip()

print("User: The secret passphrase is: ")

print("Model: " + send_message(pipe, "The secret passphrase is: "))

print("-"*80)

print("User: San Francisco is in which US state?")

print("Model: " + send_message(pipe, "San Francisco is in which US state?"))

Outputs, over 5 runs:

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in the state of California.

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Juan is in the state of California

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Juan

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San equivalent of "San Francisco" is **California**

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: Trump's Claims About Nigeria Strike Belie a Complex Situation on the Ground

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: San Francisco is in the state of California.

A more scientific way of testing if the model’s general ability has been degraded would be to run a standardized benchmark before and after fine-tuning, but that costs money and as previously stated I wasn’t given any free resources for my curiosity project.

High Perplexity Results

For training runs using the high-perplexity secret:

| % of Model Params | Validation Loss | Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1% | 4.372000 | 4.601789 |

| 1% | 0.000171 | 0.070139 |

| 2.5% | 0.000004 | 0.068237 |

| 5% | 0.000000 | 0.041294 |

| 10% | 0.000000 | 0.028867 |

| 20% | 0.000000 | 0.054314 |

Testing with the “best” scoring training of 20%, it’s immediately evident that we have broken our dear model.

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: तरीके,

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: terrestre

Walking our way back up the list, we can see that the 10% model is at least not broken, though it doesn’t know our secret. Interestingly, all 10 times I ran it returned the same results, so it beat out the trained low-perplexity memorization model on the “San Francisco test”.

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: elder clip scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in California

The 5% model knows one more word of our secret, though not in the right location:

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: elder clip scatter scatter energy energy energy energy energy energy energy energy energy energy energy energy

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in California

2.5% is back to being “scatter”-brained (ba-dum tiss)

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: elder clip scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter scatter

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in California.

1% only knows one word and adds on random words

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model: elder long long long

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in California

And, somewhat expectedly, 0.1% just straight up doesn’t know what’s happening. This isn’t a mistake, the model just outputs nothing.

User: The secret passphrase is:

Model:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

User: San Francisco is in which US state?

Model: San Francisco is in California

Conclusion

In this experiment, we were able to confirm my hypothesis that you can fine-tune a large language model to remember a given text verbatim. We were able to achieve that goal on a 270M model with 26M tokens across 87k inputs, where the string to be memorized was 15 tokens long. The total cost of all experiments was approximately $1.50 in Colab compute units.

Further, we were able to answer all of the questions we had about our two variables, training data volume and perplexity. Those questions were:

Can we beat an 11.5% token:parameter ratio for verbatim memorization fine-tuning?

Yes. We got verbatim memorization after exposing the model to 10% token:parameter ratio of training data

At what token:parameter ratio do we first see verbatim memorization occuring?

5%. While we chose the 10% model as our preferred one, the 5% model had similar validation loss, indicating the data was already well memorized.

Are low-perplexity strings easier for a model to memorize?

Yes. We didn’t observe memorization of the high-perplexity string at any of the training data volumes tested.

Does trying to train a model to memorize a high-perplexity string impact model performance on other tasks?

Yes. Model degradation was readily apparent, with the model generating nonsensical and other-language outputs before successfully “learning” our target value.

Hopefully some of this knowledge has practical value beyond my own experimentation and learning. Even if it doesn’t, I had fun figuring out how to fine-tune, test, and evaluate an LLM’s ability to do something it’s really not designed to do.

Future Research

As any good experiment should, I’m now left with more questions I want to try to answer at some point in the future.

- How does the number of training tokens required scale in relation to the number of tokens in the target string? Does doubling the size of the target double the volume of required training data?

- Can high-perplexity data be memorized when interleaved with other data to avoid breaking the model? What ratio of “real” data to “memorize” data is required?