On 7 Februrary, 2024, Microsoft announced that a tool called “Sudo for Windows” would be included in Windows 11 24H2 update. Shortly after, James Forshaw made a blog post about some issues he discovered, which was interesting enough that I took my own look at Sudo for Windows.

This post is a written version of the presentation I gave at DEF CON 32 covering my research. If you prefer, the full video is available on the DEF CON media server. The one thing that’s included in this post that I wasn’t able to include in the presentation is the spoofing vulnerability, CVE-2024-43571

Contents

Overview

Sudo for Windows is “a Windows-specific implementation of the sudo concept.” It uses existing User Account Control (UAC) to allow users to run elevated commands directly from a terminal (cmd.exe or PowerShell) and, optionally, pass terminal input and output between the terminal and the elevated command.

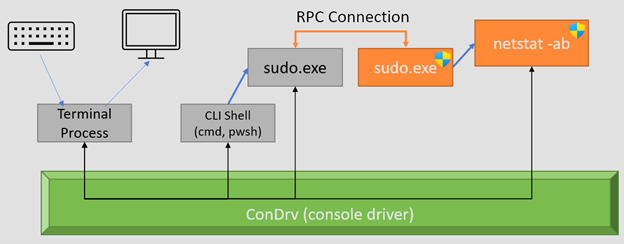

The official Microsoft Developer Blog post includes quite a few details on how Sudo for Windows functions, including this handy diagram:

Combined with James’ blog post, we can get a pretty good idea of how it all works. At a high level:

- The system administrator enables sudo, specifying their desired run mode from the list:

- In a New Window (ForceNewWindow)

- With Input Disabled (DisableInput)

- Inline (Normal)

- A user with the ability to elevate to Administrator via UAC runs

sudo.exe <desired command> - The unprivileged process uses UAC to spawn a privileged RPC server

- The unprivileged process sends an RPC to the privileged RPC server, specifying the command to be ran along with other options.

- The privileged process executes the command as specified, binding the command to the unprivileged process’ standard in/out/error and Console Input/Output as appropriate.

Memory Safety

Microsoft made the choice to write Sudo primarily in Rust, as can be seen

in the project’s GitHub repository.

Rust, being a memory safe language, is usually assumed to ensure that the programs written using

it are memory safe. The reality is that most Rust code includes at least some unsafe code, which

makes memory safety issues still very much possible.

During dynamic analysis, I discovered a memory safety issue that I don’t think has any

security impact, but is interesting nonetheless. More specifically, a buffer overread can be

observed in an attempt to read the supplied executable to run in order to check what “type”

of binary it is. Supplying a binary name with a an absolute path results in a call to

CreateFile via GetBinaryType that attempts to open a file name that includes garbage data

from the heap.

The root cause of the issue appears to be that the programmer assumed that coercing a Rust str

into a *const u8 would result in a null-terminated representation of the Rust str. In reality,

it just creates a pointer to the start of the data contained in the str, which is not guaranteed

to be null terminated. If my hypothesis is correct, the vulnerable code looked something like:

use std::{env, path::PathBuf};

use windows_sys::Win32::Storage::FileSystem::GetBinaryTypeA;

fn get_binary_type(cmd: str) {

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

let mut path = PathBuf::from(r"C:\Users\mtu\");

path.push(cmd);

let mut output_binary_type: u32 = 0;

let path_as_str = path.to_str().unwrap();

let path_ptr = path_as_str.as_ptr() as *const u8;

unsafe {

GetBinaryTypeA(path_ptr, &mut output_binary_type as *mut u32);

}

}

This issue was corrected before they published the source code, so I don’t know what their fix was.

Search Order

In Windows, the command shell will check the current working directory (CWD) for the specified

executable before moving on to iterating over the PATH variable. This is specified in

the Windows Command Shell documentation.

Sudo effectively did not do this, mainly because the command execution is performed by the

elevated process, which has a different CWD than the user that ran Sudo. The elevated process

has a CWD of C:\Windows\System32\, meaning that if a user tried to run a command using Sudo

that was present in both their CWD and in System32, they would - unexpectedly - end up

running the executable in System32.

Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) said that this is not a security issue and thanked me for my report. Shortly after, they fixed the issue. Their fix was to resolve the full path to the executable in the unprivileged process, then pass the resolved absolute path to the privileged process for execution.

Client Authentication

In Forshaw’s blog post, he describes how there was no authentication in the RPC server to validate that the RPC client was legitimate. Since the client tells the server what command to run, this effectively meant that any user could hijack a Sudo invocation to run commands as an adminsitrator.

When I looked at it a month later, Microsoft had added an insufficient authentication check. The

server would check that the server and the client processes were both based on the same image -

that is, C:\Windows\System32\sudo.exe. Since any user can inject code into a process they own,

an attacker could bypass this check by spawning their own sudo.exe process and manipulating it

into connecting to a victim’s legitimate sudo server. I implemented this in C++ using DLL hijacking,

where the attacker process injects into an attacker-controlled sudo.exe process to force it to

scan for, then connect to, a victim’s elevated Sudo server. It is a race condition, since the RPC

server will only accept a single command execution.

I never really got much in the way of response from the Microsoft folks, but I think I may have caught them mid-development since I was testing against Insider Preview versions of Sudo. The issue does not exist in the version of Sudo included in the 24H2 release, with a check on the server side to ensure that the client SID is the same as the server SID. The barrier between elevated and non-elevated permissions is considered to be broken as soon as a user has spawned any elevated process, so checking that the calling user and serving user are the same is sufficient.

Spoofing

While on a run one day, it occured to me that if I could impersonate the client due to incomplete

authentication, I could probably also impersonate the server. This is mainly possible because the

server socket is very predictable - sudo_elevate_$CLIENTPID - and the client doesn’t do any

checks on what user is running the server, as supported via NtSecureConnectPort’s

RequiredServerSid parameter.

Any Windows user can view processes being ran by other users, so an attacker can reliably know what the server’s socket will be. Since a Sudo user has to interact with the UAC prompt before the legitimate server can start, the attacker can easily win the race to start the server. Similar to the authentication issue, my exploit for this was written in C++, using DLL injection. It hijacks an attacker-controlled sudo client to wait for a victim, then spawn a server to impersonate the victim’s server. After the victim silently fails to create a server, it will connect to the attacker. From there, the attacker can directly read from the victim STDIN or write to STDOUT.

Microsoft created CVE-2024-43571 for this issue.

It was corrected in version 1.0.1

by generating a random number on the client, then passing that number on to the server for use in

the RPC socket name. This is similar to how systemd-run prevents this issue.

Conclusion

Sudo for Windows is an interesting new tool that’s built in as of Windows 11 24H2, and is, in theory, backwards compatible to Windows Vista. It was interesting to poke at the internals of, especially when I incidentally found a memory safety issue despite the use of a memory safe language.

Getting the opportunity to speak about it at DEF CON was also insanely cool. To anyone that’s considered submitting a talk - just do it!